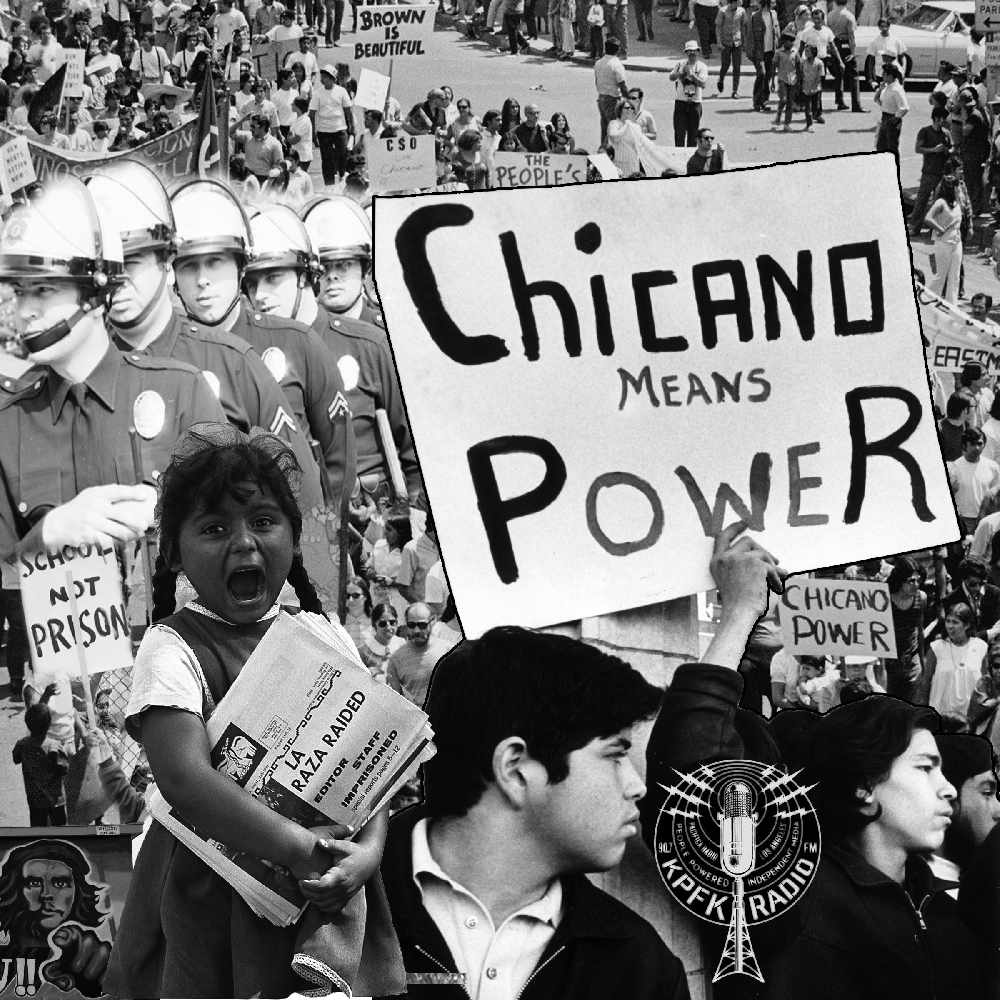

Images courtesy of UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center. Photo collage by Ernesto Arce

By Ernesto Arce | KPFK News

Hundreds of people gathered across East Los Angeles to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium, the largest anti-war protest in the city at the time. Although the crowds were impacted by the coronavirus pandemic, many marched, walked, skated, and even drove in a car caravan retracing the route of the original march.

On August 29, 1970, more than 30,000 Chicanos took to the streets of East LA to say: No More War in Vietnam. They were also demanding the right to self-determination for Mexican-Americans of the U.S. southwest, its own nation & culture within this diverse country.

The march and rally was violently broken up by the LA County Sheriff’s department and other law enforcement agencies. Four people were killed including journalist Ruben Salazar, considered the voice of the Mexican-American community, which compounded the community’s outrage with the city’s largely white status quo. About 150 were arrested and many suffered injuries.

Some of the faces from the 50th Anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium. (Photos by Ernesto Arce)

As a journalist for Pacifica and the KPFK News, I was granted access to the LA County Sheriff's Department secret files on the Chicano Moratorium and its organizers and key activists ten years ago. This was a result of the Los Angeles County Office of the Inspector General reopening an investigation into the incident 40 years later.

Former LA County Sheriff spokesperson Steve Whitmore gave me about two hours to peruse the files, just him and I. He was there, he told me, to supervise the files and to ensure that nothing was photographed or taken. Fair enough.

What did the files reveal? The Sheriff's Department was watching everyone. Chicano celebrities like Ricardo Montalban, Vicki Carr, Anthony Quinn, Linda Ronstadt, and Joan Baez were being monitored. Mexican-American politicians and community leaders were, too. But law enforcement was most interested in the militant movements of the day: La Raza Unida Party, the Brown Berets, Communist Party USA, Socialist Workers of America, were all specifically named as instigators and fringe groups that might engage law enforcement in violence.

The PLP, the Progressive Labor Party, was a communist organization that was making inroads in the Chicano community. Most files in the two or so boxes that I had time to go through dealt with that group. The files show evidence that PLP was infiltrated, spied on, and most likely targeted by undercover operatives.

But the biggest shock from those files that left me speechless were the coroner's photos of Ruben Salazar's dead body. The tear gas canister missile blew a four inch-diameter hole through his head. Missile is the only way to accurately describe what literally blew Salazar’s head open. I had to take a second to compose myself as Whitmore peered over at me.

The OIS actually reached out to the Sheriff's deputy who reportedly fired the missile into the Silver Dollar bar that day. The former lawman, retired somewhere in the midwest, swore he didn't know who Salazar was and didn't intend to hurt him.

But over the years of covering subsequent moratorium commemorations, many people in the community – and maybe all activists in the movement - don't believe that story. They insist the powers that be wanted to silence Salazar's voice forever.

But activists would remind the news media that it wasn’t about just one man, as important a figure as Salazar was to the community.

It was about an oppressed people that were clamoring for justice.

A young Brown Beret commemorating the Chicano Moratorium in 2015. (Photo by Ernesto Arce)

Carlos Montes, with the Centro CSO, helped organize the original moratorium, perhaps the most pivotal moment in Mexican-American history.

“50 years ago we were organized. We were protesting the war in Vietnam, racism, police killings and we had a great mass movement,” said Montes, wiping sweat from his brow after a long march on a hot day. “I see a new wave of Chicano activism. Today I feel exhilarated that a whole new generation is taking on a new wave of activism that started with Black Lives Matter.”

The younger generation is also finding out about their history.

Ismael Salazar of Lincoln Heights says he’s indebted to the Chicano movement for having laid down a path for newer generations.

“I feel like they’ve done a lot already. And I’m here to pay my respects,” said Salazar. “I feel like my educational path was facilitated. I was able to graduate and I had enough resources and I feel they had a part in that.”

Many of the participants of the weekend’s march were elders who remember the Moratorium.

Mary Cladoris and Yvonne Sandoval were children at the time. They both grew up in nearby Boyle Heights and said they have clear memories of watching the moratorium march pass through the streets.

“We’re here 50 years later and a lot of the problems still exist but a lot more of the younger generation has a consciousness of what’s going on,” said Cladoris.

A protest against the Sheriff's department for the killing of 14 year-old Jesse Romero in 2016. (Photo by Ernesto Arce)

Sandoval said she took part to honor those who fought for Chicano rights “and to understand that these new killings of our boys is… too much violence por nada and I”m appalled but I’m here to fight against it.”

Much like then, Chicanos were dealing with poverty, high unemployment, lack of educational opportunities, and police terror that criminalized brown-skinned youth particularly hard. And when it came to the Vietnam War, Chicanos suffered about a fifth of early wartime casualties while only making up about 8 percent of the population.

Arron Carrillo with the United Brown Coalition called it a beautiful event.

“Not everyone has the luxury to be taught this. I had to educate myself on it,” said Carrillo. “Once I found out, it sent me on a journey to self-identity. It’s also a self-love journey; a self-healing journey.”

The 50th Chicano Moratorium commemorated the march’s original demands. Safety precautions taken for the coronavirus pandemic meant smaller crowds than expected and lots of people who were relegated to a sizable car caravan.

Still, the mood was celebratory and defiant, just like back in the day.

-

Farewell to Sister Assumpta Oturu, Champion of African Voices

Farewell to Sister Assumpta Oturu, Champion of African Voices

Celebrating the life and legacy of Sister Assumpta Oturu, who amplified African stories and built bridges across continents through decades of fearless broadcasting.

-

Cary Harrison Explains The Truth Behind The Mar-a-Lago Raid

Cary Harrison Explains The Truth Behind The Mar-a-Lago Raid

What would George Washington say? Secretly flying 35 filing cabinet drawers-worth of Pentagon secrets to your private hotel for favor-swaps was the straw to make all Presidents now raidable. Will this affect a future Trump 2024 run? What about Hunter and Hillary?

-

The Cary Harrison Show, Tuesdays at 2PM

The Cary Harrison Show, Tuesdays at 2PM

Check out Cary's latest episode, including an interview and memories with the iconic actress Nichelle Nichols!

-

The Cary Harrison Show, every Tuesday at 2PM!

The Cary Harrison Show, every Tuesday at 2PM!

The Cary Harrison Show, July 12, 2022 - Cary Harrison explains why the Jan. 6 hearings really matter! And Dr. Christopher Davis on stress and your heart.